Zack Davisson is an award-winning translator, writer and folklorist. He is the author of Yurei: The Japanese Ghost, Yokai Stories and Kaibyo: The Supernatural Cats of Japan, and the translator of Leiji Matsumoto's Space Battleship Yamato, Go Nagai's Devilman, and Shigeru Mizuki's Kitaro.

He was nominated for the 2014 Japanese-US Friendship Commission Translation Prize for his translation of the multiple Eisner award-winning Showa: A History of Japan. He has lectured on translation, manga and folklore at Duke University, UCLA, and University of Washington, as well as contributed to exhibitions at the Wereldmuseum Rotterdam and the Art Gallery of New South Wales. He has been featured on NPR, BBC, and The New York Times, and has written for Metropolis, The Comics Journal, and Weird Tales Magazine.

He is the translator of recent release Sōseki Natsume's I Am A Cat: The Manga Edition. On this International Translation Day, we sat down with Zack to chat about his latest project.

How did you begin your career as a translator?

I got my master’s degree in Japanese while studying in Hiroshima, and that included translation as part of the program. I found I enjoyed translation, specifically the challenges of literary translation. I started a website, hyakumonogatari.com, where I translated Edo period yokai stories and weird tales. That gave me the experience I needed to do it professionally, and I was able to start my career translating Shigeru Mizuki’s comics. My first translations won two Eisner Awards, and things have gone forward since then!

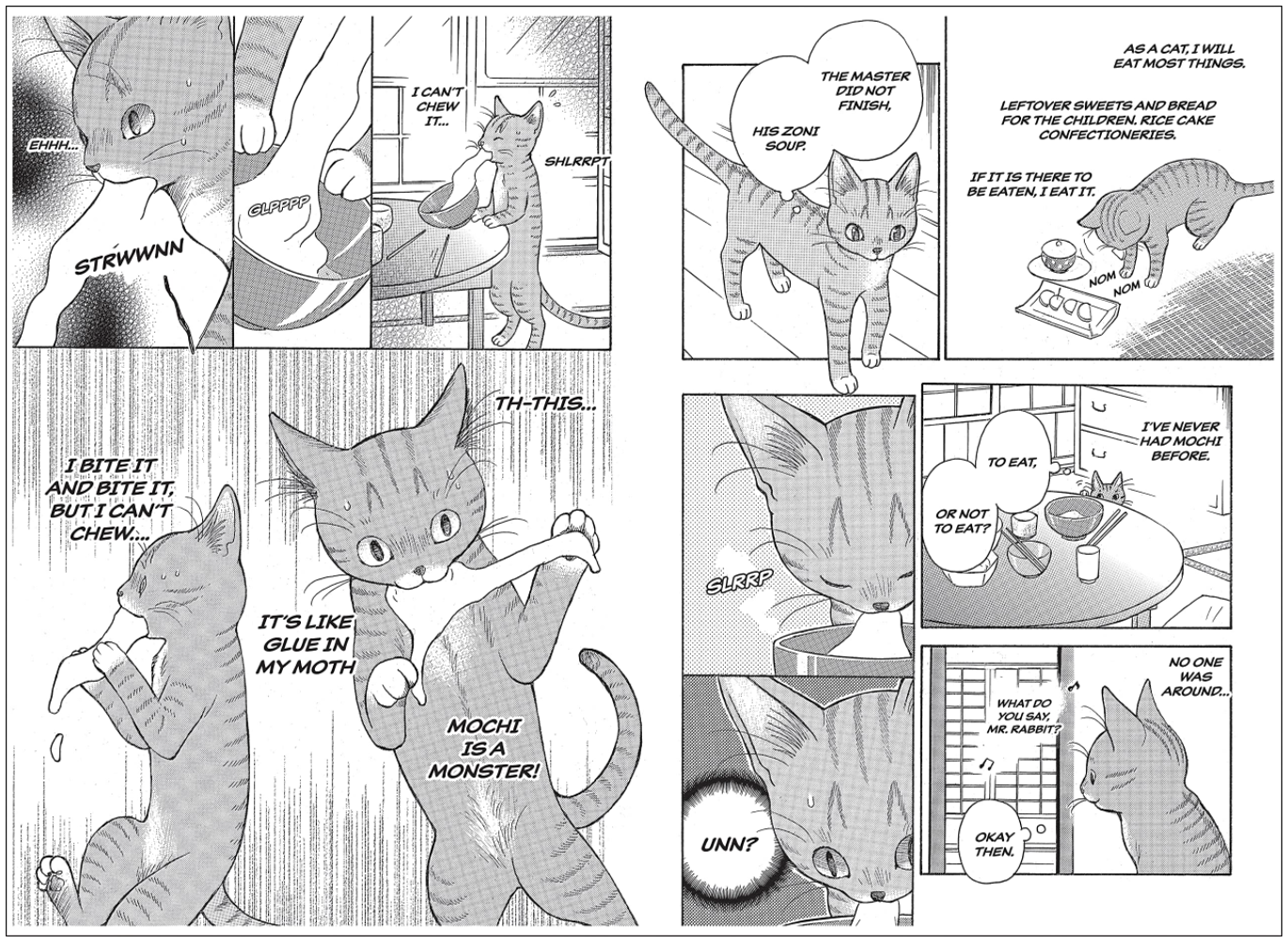

Did you encounter any particularly memorable lines while translating Sōseki Natsume's I Am a Cat: The Manga Edition?

I enjoyed doing the different personalities, especially the cat Kuro. I was translating I Am a Cat during the height of the pandemic, and there was a line where Kuro was talking about New Year’s Day. He says, “As if one good day makes up for the rest of a pointless year.”

That resonated with me a little too much!

Sōseki wrote the original I Am a Cat during the Meiji period (1868 - 1912). Did the narrator’s dated Japanese present any challenges for you?

Most of my translation practice was done on Edo period literature, so Meiji period wasn’t too difficult! I enjoy classic literature in my personal reading, so this sort of thing comes naturally for me. The challenge is in preserving the voice while still making it readable for modern readers. As someone who specializes in classic manga I think this is something I have a particular talent for. I hope readers agree!

Why do you think I Am a Cat continues to resonate with readers today?

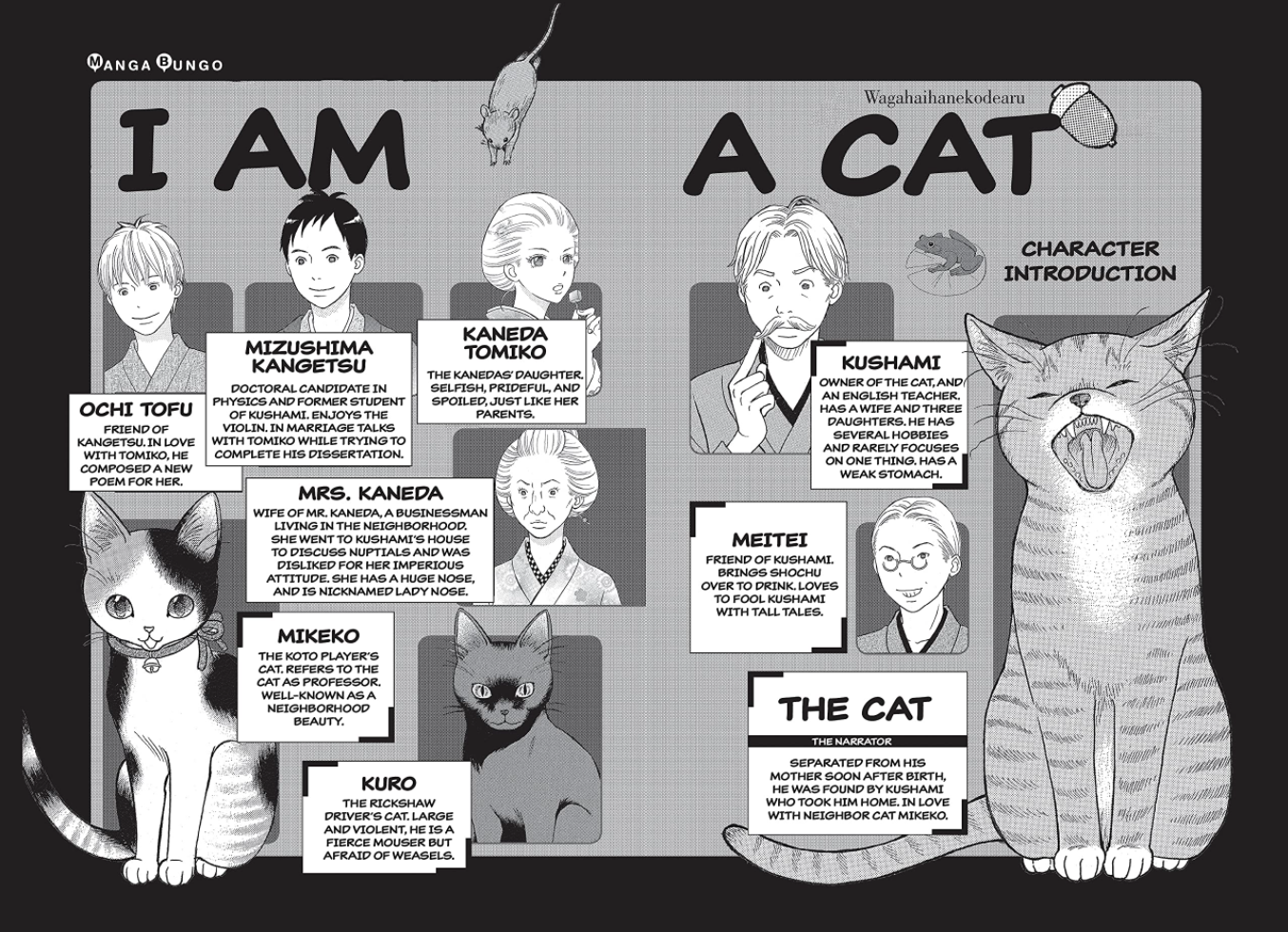

If there is one thing I have learned in my career, it's that cats will always resonate with readers! The use of the cat as the viewpoint makes I Am a Cat as inviting as when it was written. And then themes inside are sadly universal. Money is still more powerful than knowledge. Love is still complicated. Death is still merciless and sorrowful.

I personally think that one of the things that makes work like this so interesting is that they show how little the human condition has changed across centuries and geography. With barriers of language and culture removed, people are, at their hearts, people. And cats will always be cats.

What is one common misconception people have about manga translation?

That it is an technical job, not an artistic one. Translators have their own voice, their own style. A translation is a lot like doing a cover version of a song—its always going to be different from the original. Two different translators will produce two different works.

How do your processes for translating prose and manga differ?

This question is easy to answer—real estate. In prose translation, nobody cares if the page numbers match. A 280-page book in Japanese can become a 320-page book in English, or a 250-page book in English, and no one will bat an eye. The length is mutable. But with manga, not only is the page count absolute, so is the space on each panel. The word balloons only have so much space, and everything you do has to fit into that space. There is very little flexibility!

There are other differences as well. Manga is almost entirely dialog, whereas prose fluctuates between dialog, description, and exposition. So you have to have solid skills at dialog to succeed in manga. Making it sound natural is the key. The goal is to have a finished work that sounds like it was originally written in English.

As always, it is up to readers to decide if I succeeded!